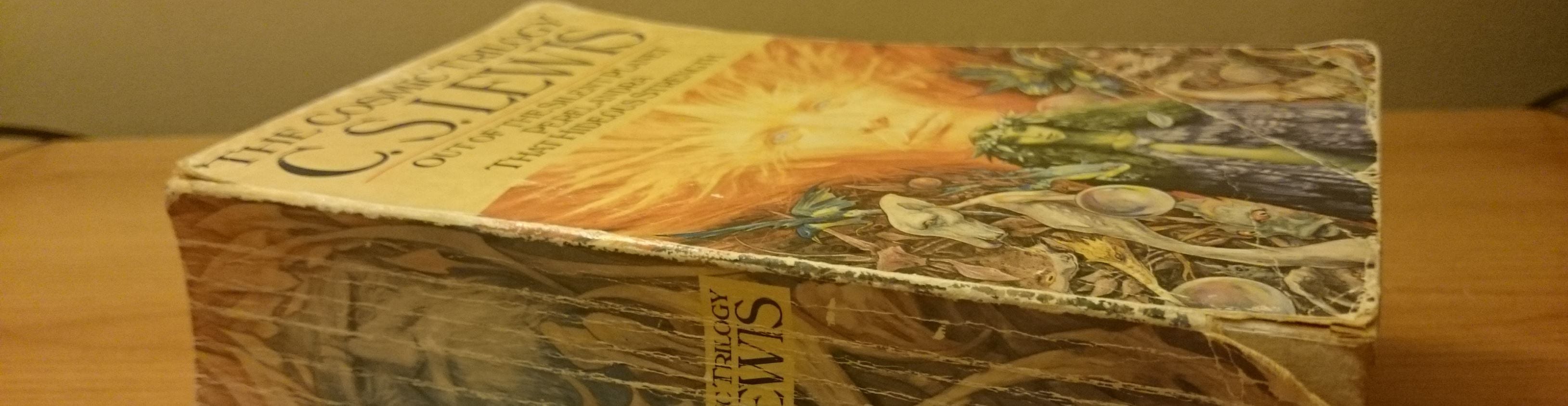

Perelandra was not my first encounter with C.S. Lewis, yet I was once again struck by his imagination, clarity and great theological insight in the Space Trilogy. Though following Out of the Silent Planet and preceding That Hideous Strength, Perelandra could be read by itself.

Lewis’s Space Trilogy was the first science fiction in my reading life. Before this, I had never imagined I could see any possible fusion between imagination and faith. Perhaps I had been more engaged in time-travel with J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, so known very little about space-travel and its relation to truth, myth and fact. But when I found myself transported to Malacandra and Perelandra, my imagination was baptised, my telescope extended, and my mind broadened and deepened into the Gospel itself. By Lewis’s brilliant storytelling, I was drawn into the mysteries of Maleldil, the Oyarsa, the Green Lady (the Eve figure), Ransom (the Christlike figure), and Un-man (the devil figure). These stories did not just entertain, yet they invited me to think again more widely and deeply about creation, grace, sin, pleasure and freedom.

Below are some reflections on how Lewis influenced me and helped me rediscover and better understand God’s purposes through the stories.

Revisiting Eden

Perelandra, or Venus was Lewis’s brilliant attempt, by embedding truth in wonder and awe, to rethink, reimagine and retell many parts of the Genesis story. When I first glimpsed the world of Perelandra, I was instantly reminded of what Tolkien, in his remarkable essay, On Fairy-Stories, said of Recovery. Recovery means to regain a clearer view of something—seeing the familiar as both strange and more truely again. It has long been noted that things too close and familiar to us are the ones that we find most difficult to clearly see with fresh eyes. The triteness of what we know too well, strips us off our ability to perceive its value, uniqueness, even oddness and unlikeness.

The book of Genesis, for many Christians, has been undoubtedly familiar—perhaps too familiar. But I with the utmost daring discover that the more we are familiar with it, the more we begin to complaint the dullness of it. But Perelandra is a book that not only drives me to return to read Genesis with a magnifying glass, but also makes me feel, so to speak, like an odd person—It is a joke, but it is not against me. Lewis helps me, odd as I am, to see the oddities of God’s creation and the terrible reality of sin. Having journeyed to Perelandra and come back to reality, I have found Genesis is no longer dull, but rich, otherworldly, divine and alive.

Through Ransom’s encounters with the Green Lady and the Un-man, Lewis teaches me to see from fresh angles, as though I were standing on my head, the Good and Evil in the Eden. What Lewis is doing in the Perelandra is inviting us to revisit Eden through the medium of science fiction. The goal is not merely to see another world, and also to be taken by Lewis’s imaginative eyes to contemplate what occurred before the Fall of Adam and Eve.

Indeed, when we are in Perelandra, it is important to be drawn into the story and let all to unfold . It brings us back to the most fundamental and primary questions: What is God’s creation? What is sin? How do they conflict and impact us? When I was reading this, I set myself up as a traveller and stepped in between the main characters. Ransom, whose very name suggests salvation, is a good man in great danger and the only one who strived to defend the truth, goodness and beauty of God against Weston who is possessed by the Un-man, a Tempter. The Green Lady is Eve, unfallen figure, living pleasantly and freely in the sinless Perelandra.

One of the most striking to me about Perelandra is its floating islands and its ever-rolling oceans. These islands are home to various kinds of strange and merry beasts and birds, hosting fantastically shaped and coloured mountains and valley, clothed in many-coloured forests, and dotted with flowers and plants of blissful fruits. Importantly, the surfaces of the islands are shifting and moving, never anchored, yet perfectly conformed to the shapes and waves of the ocean. When I was reading these, I found this world quite unsettling, and asked myself why should such an Eden-like world feel so unfamiliar and uncertain? But later, I realised that Lewis was trying to take us to a place that should look both uncertain and safe. Though the islands are constantly moving, but they are still friendly and liveable. Lewis reassures us that they pose no threat and there is not any sign of danger noticed there. Lewis helps us see that peace and uncertainty, wonder and danger do not necessarily contradict each other in a sinless world. There is no fear, because there is no evil.

Pleasure and self-restraint

Pleasure is another significant theme Lewis tries to explore in Perelandra. In Perelandra, pleasure is not what we often define or experience in our own world. It has many different types of pleasure but that are not driven by mere appetite or lack, but by something richer and stranger. Through Ransom’s experiences, we are invited to understand pleasures that can’t be attained by our craving: the pleasure of tasting the ocean without being aware of thirst, of smelling the flowers without feeling hungry, of being moved by beauty without a need to possess it. They are rather “new kind” of pleasure. The most particular example is the fine clusters of bubbles hanging on the bubble trees. Although there have delightful drink and blissful food for one to experience, Ransom decidedly chooses to restrain. Though he could have returned to taste again and again, he chooses not to.

Lewis offers us, through Ransom, a window into the deep theology of pleasure. Through Ransom’s self-restraint and his refusal to seek encore, here we begin to perceive a deeper principle that to taste the heavenly pleasure must require some element of resistance and restraint against the itch to grasp it over again. Below are the lines showing that Ransom perceives a deeper truth:

“He had always disliked the people who encored a favourite air in an opera — ‘That just spoils it’ had been his comment. But this now appeared to him as a principle of far wider application and deeper moment. This itch to have things over again, as if life were a film that could be unrolled twice or even made to work backwards… was it possibly the root of all evil? No: of course the love of money was called that. But money itself — perhaps one valued it chiefly as a defence against chance, a security for being able to have things over again, a means of arresting the unrolling of the film.”

Ransom reflects that our itch to have pleasure over again is merely for the repletion’s sake. Money, as he sees it, traps us into the illusion of securing the encore. We’re itched to resume our pleasure, so we risk blocking ourselves to receive true joy rightly without craving for more.

His decision to restrain reminds me of Lewis’s insights on the subject of temptation in Mere Christianity. Lewis is clear that we in fact know very little about temptation, because we give in to it too quickly and can’t resist long enough to be able to understanding it. We only begin to understand temptation when we begin to resist it. As the Kind says later in Perelandra, “We have learned better than that, and know it more, for it is waking that understands sleep and not sleep that understands waking.” Sheltered in the pleasure, one is too close to fully see it. It is when pleasure is treated with self-restraint that we can truely celebrate the true good. Pleasure on repeat would be, just as Ransom says, “like asking to hear the same symphony twice in one day.”

This, “itch to have things over again” is a part of our fallenness, for we are living in a world where we are broken, so we pursue pleasure over and over again. Lewis in this part calls us to receive each good as if it were the only good, rather than seek encore after encore. Gratitude is not that of craving for more, but of recognising the goodness of what is given once. We are encouraged to say less, “Again”, but more “That’s good enough, thank you.”

Freedom

Freewill is also significant theme Lewis explores deeply in Perelandra. The Green lady, presenting Eve in her pre-fall state, gives us a rare glimpse into what life has been like before sin entered the world. Through her conversations with Ransom, one could possibly witness a type of freedom, innocent, unspoiled, and not tainted by rebellion but perfectly aligned with Maleldil’s will.

What struck me most is the Green Lady’s response to Ransom’s talkings and his way of thinking. The Green Lady realises later that Ransom is vastly different—“more than two kinds of fruit,” and “more unlike than two tastes.” The difference is great and each of two are so great. Ransom comes from a world that chases after what it expects to be good; The Green Lady, in contrast, has been looking only for the given good—not what she expects. And it is from her own heart that she desires this.

When I was reading this part, I came at length to realisation that freewill did exist before the Fall. The Green Lady chooses to seek the true good, paradoxically the given good, not out of obligation, but trust. Ransom couldn’t see the wonder and glory of it, as it defies the Earth’s logic that true good should be as expected. But the Green Lady said,

“I thought that I was carried in the will of Him I love, but now I see that I walk with it. I thought that the good things He sent me drew me into them as the waves lift the islands; but now I see that it is I who plunge into them with my own legs and arms, as when we go swimming.”

The Green Lady understands that she is willingly walking alongside the Maleldil, not merely being carried by Him. This is where Lewis begins to astonish us—he is defending freewill. It is not the kind we use as a mean for our own sake, but as the joyful choice to align one’s will with the will of God. Risk is not in surrendering our will, but insisting on our own path. The Green Lady, though living with full possession of her freedom, has never departed from her trust in Maleldil. The danger in Adam and Eve is not the fruits itself, but the failure to obey God’s will. Sin would not have come because Adam and Eve ate the fruit, but because they defined good for themselves. I venture to say that if only they had endured successfully and waited till they’re given permission to pluck the fruit, sin would have found no way to enter. It was in choosing their own destiny that they corrupted the goodness of their life.

Frodo’s life, too, reflects this truth. When he says, “I wish it need not have happened in my time.”

Frodo does not change the course of his own future by rejecting the Ring. Instead he receives it and bears it freely, though reluctantly, choosing to take a costly path for the sake of the Shire and of the Middle-earth. Gandalf, echoing on the weight and wonder of the rightly used freewill, says, “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

In the same way, the Green Lady shows that freedom is not for choosing the expected good, but instead for receiving the given good, and trusting that the good given by God is the best.

Lewis’s Space Trilogy couldn’t be long enough to suit me, for I found it so enthralling and spiritually nourishing. Lewis might be best known for Mere Christianity and the Chronicles of Narnia. But I would say that his Space Trilogy is a hidden gem, for one cannot help but marvel at his brilliant storytelling in fusing reason, faith, imagination, and the profound truths of God’s grace.

Thank you for your post. The delight in trusting God for the best, not just the best considering the situation but rather the best!

Stanley this was a great reflection on perelandra! Thanks for writing this. Like you, the theme of free will stirred me in my reading of Perelandra. One of my favorite quotes from the lady is “to walk out of his will is to walk into nowhere.”

I’ve been on a break from my substack podcast however when I get back to it, it would be fun to have you on for a session on perelandra.